Thanks for joining us again. I promise that this will be the final chapter of our US trip and what a fine finish it is. If you’re new to the blog, this post is part of a series that starts with Cruzin’, then Cruzin’:Day Two, Cruzin’ III:Mexican Adventures, Cruzin’ Day IV:Poison & Magic, Last Day Cruzin’ and NASA! This is another 3,000-word whopper but I’ll try to cut most of the slack before publishing. It’s mostly photos anyway.

It’s a long jet-ride from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts of the US but we landed at LAX OK. Next job is to get to the hotel. No airport train, no public transport (that would be Communism!) so it’s an Uber to Anaheim. Trouble is that you do have to take public transport, an airport bus, I don’t know, 55 miles or something to an enormous carpark that is the Uber pickup zone. The ten acres of tarmac and tents looks like it was set up five years ago as a temporary refugee camp and forgotten about. LA is a bit of a shithole but it’s better than some shitholes I have been in.

Into our Uber and a ride down massive elevated highways covered in wicked skidmarks (Look Sachie! That one goes over four lanes!) for a $60 trip to the JW Marriott, just a stone’s throw from Disneyland.

The JW is a premium brand. The front-of-house is very nice and staff are polite. The room was complete balls though, more fitting for a motel. Dinged up furniture, handles and knobs falling off drawers and, what irritated me the most is that the mattress was a size smaller than the base, so I’d see the the mattress, in line-of-sight, then kick the corner of the much larger base every time I walked past.

The couch was a pull-out single bed so I’d kick that every time I went to sit down too. Mrs Sachie is Japanese so slippers are a must but there were none in the room and they got shirty when we rang up and asked for some. The whole thing is pretty outrageous and if we were not getting the staff discount I’d burn the hotel down. The fucking cheek!

Anyhow, musn’t grumble. There is fun to be had at California Adventure. That’s the park opposite Disneyland and we’ll try that today before the main event tomorrow.

Both parks are done up for Halloween and some park-goes are already in costume. It was the first of October.

And here we are inside, with dear old Uncle Walt.

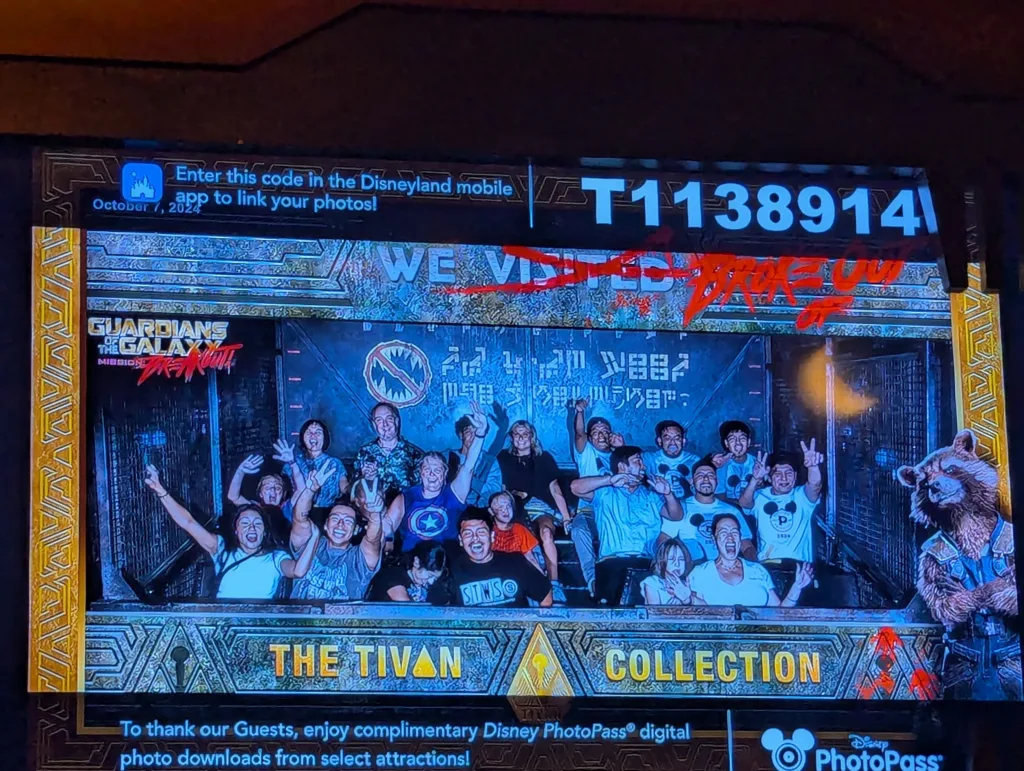

First ride is Guardians of the Galaxy. It’s one of those ones where they put you in a big lift and drop you.

My glasses floated right off my face, lucky they’re on a string. I wear them on a string around my neck because I can’t be trusted not to lose them and they’re expensive. My mother pointed out that anybody who wears their glasses on a string is “unfuckable”. Her words, not mine.

But look at that unflappable, suave chap in the green shirt at the back. While everybody else panics he is cool, collected. Fuckable.

Next up, the line ride Spider-man Web Squirters Slingers. It’s almost an hour in the queue but Disney does queues differently. They are long, but you can’t see beyond your own section. Also, you’re always shuffling forward, even if it’s only slowly. That gives one an impression of progress. There’s stuff to look at on the way too.

The last wait is to get a video presentation of Peter Parker making a mess of the lab and, well here’s the synopsis:

Embark on an action-packed adventure alongside the amazing Spider-Man! When Peter Parker’s helpful but otherwise buggy Spider-Bots get stuck in replication mode and escape from a WEB Workshop, Spider-Man must stop the rampaging robots before they wreak total techno-havoc across Avengers Campus. Problem is, they’re rapidly leveling up and becoming tough to beat!

Your task? Hop aboard a WEB Slinger vehicle and help weave a frenzied web to trap these friendly neighborhood sidekicks in true Spidey style. It’s up to you to unleash your inner hero and save the Campus from complete chaos!

You get in a pod on a track and shoot stuff as you go by. Lots of rides these days seem to be this format and I think it’s a big lame. Mostly because they keep score and I get the lowest. This one is different because you don’t have a laser-gun but make a web-slinging gesture with your wrist. I guess that’s cool but it’s no Space Mountain.

Next stop is Neo-Tokyo, Mrs Sachie’s home town.

I want to have a quick talk about our fellow park-goers, the natives. Most of the younger crowd were unremarkable but, by Christ, there’s a lot of fat fuckers walking around, most of them with kids. Some of them on little electric scooters that you can rent outside the park. I’ve written about this before but it’s a constant eye-opener in the lower-52. Being overweight isn’t easy and a skinny person should never criticise a fatty because they’re never had to deal with the problem but my doctor keeps telling me to lose weight so I reckon that gives me a pass. The Latin families were the worst. Dad looks ‘husky’, like me, but mum is massive and gets pushed about in a wheelbarrow while pushing Cheetos in her face.

In your 20’s you can eat shit food and stay, if not skinny, normal. I have a theory that people in the US eat way too much junk food when they are young and don’t change their diet when they hit 30 so just end up looking like over-inflated balloon animals. It’s pretty depressing to think about.

Here we are in Pixar land.

I was damn tempted to buy my own Bing-Bong plush toy but Sachie says I have too many teddybears already.

This is a ride, but it’s not the roller-coaster you see at the rear, it’s a spinny thing for little kids, which I think is off-tone from the movie.

I had a breather on a park bench while Sachie went off for a pee. It’s not easy being on one’s feet all day, maybe I should get one of those electric scooters? A chap with his leg in a cast that he carted around on a monocycle contraption sat next to me and naturally we got chatting. Sean’s from Oregon and busted his bone in a dirtbike accident. He was visiting with his wife and grandkids. Grandkids? He looked my age, maybe younger. Skinnier too.

Hurricane Helene had caused surprise flooding in North Carolina about a week before and he wondered aloud if it was actually caused by cloud-seeding. Hmm. I don’t think they do cloud-seeding in the middle of a cyclone, seems a bit redundant. I went on to tell him that cloud-seeding doesn’t really work, or if it does you can’t really tell, so it’s a bit stupid. I should know because I live in Thailand where the previous King had a cloud-seeding programme that was less about weather and more about a modern connection to the myth that the King is magic and can control the rain. On reflection, I probably came across as weird to him as he did to me.

Oh well, now it’s time to retire to…

Radiator Springs. Scene of the fever-dream movie Cars and just the place to be when the sun is low and the mushrooms are kicking in.

Yep, I’m totally feeling it now. Far out…

But the sun really is going down, it’s getting dark and we started the day on the other side of the continent so it was time to find food, booze and bed. Ideally in that order.

On the way out, Sachie took a photograph of this beautiful sunset.

Silly Sachie! Can’t you tell this is a backdrop? It’s obvious to me.

We had stopped at a Denny’s for lunch on the way over but couldn’t go back. I don’t qualify for the 55+ menu and we didn’t tip. Luckily…

Dumplings my favourite! And Michelin recommended, awesome!

It’s a weird place. Walked in and asked for the menu and the bloke behind the counter gestured to a big touchscreen. OK, did our order. Pay by credit card? OK… tip? What the fuck am I tipping for! A computer’s taken my order and I haven’t even eaten the food yet! Who am I tipping!?

Turns out the dumplings were just OK but a bit sweet, which is not what you want in a soup-dumpling. The savoury pancake I had was cooked in yesterday’s oil and gave me squirts the next day. Bib Gourmand indeed!

Fuck it. It’s a new day and here’s Sachie with a box of chocolates. Got some big shoes to fill there Sachie.

We got off to an early start, because the bedside alarm went off at 4:30am! I swear to God, hotels in the US really are rubbish. Breakfast was in the lounge (we visited last night but you have to pay for drinks! Rubbish!) and a bit pedestrian but the strawberries were a treat for us.

We made up for the top-dollar, modest-service by stealing all the muesli bars and fancy Italian water. We still have a few in the cupboard today, years later. Now off to the main event, Disneyland!

Even with our early start we didn’t get there until nine and the crowds were already a-swirl.

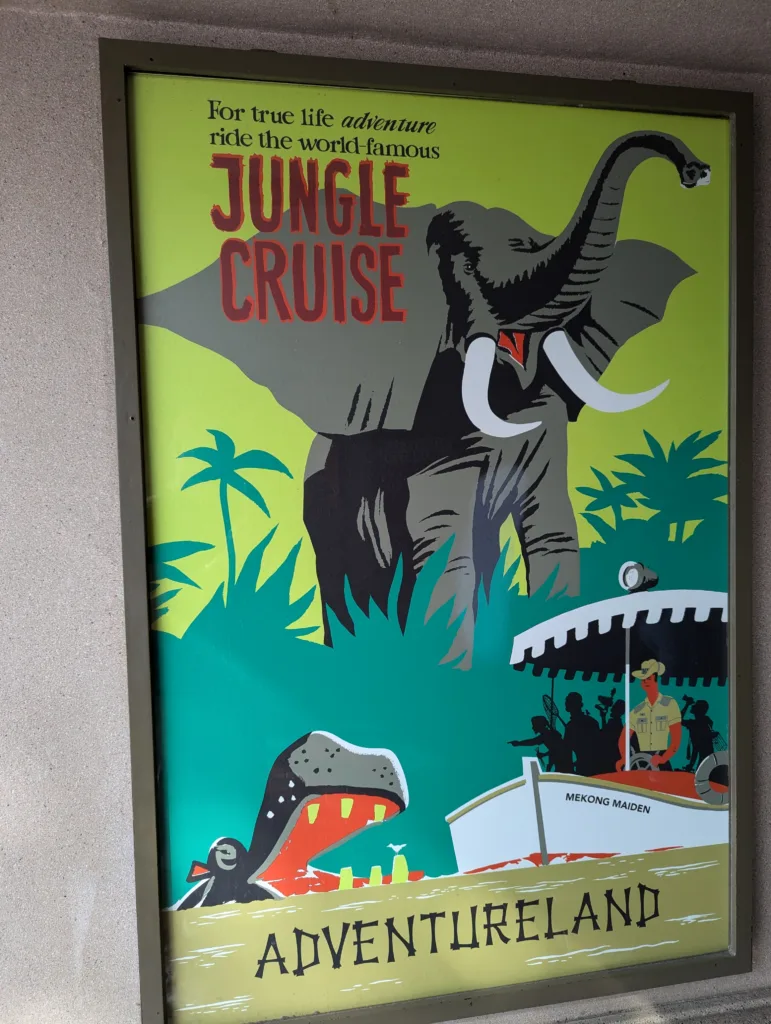

There are old-timey posters to look at while you queue up. This looks good.

Isn’t that s sulphur-crested cockatoo?

Totally going on this one.

Disneyland’s famous railway station was under renovation. This was a big disappointment as, when we went to Tokyo Disney, Sachie and my kids wouldn’t let me ride the train. All I wanted was to ride on the choo-choo but they wanted to go on the roller-coaster. The train goes puff-puff and the whistle goes toot-atoot. And now I can’t go on the train. Again. I’m going to cry. The nag and her cart are a poor substitute. I hate you! I hate you all!

Sachie gave me her hanky and told me to stop being a baby but I refused, so she took me to Adventureland. This looks good.

Looks like we are back at Ankor Wat. I wonder if that postcard kid who ripped me off in 2001 is still around?

One long queue later we’re on Jungle Cruise. We did this one in Tokyo and the movie based on it isn’t that bad. More yuks than African Queen anyway.

I was keen on this one as it’s the OG but I must say that the one in Japan is better. This one has a wisecracking American teen at the wheel with a pistol. In Japan it’s a hot girl with a sawn-off shotgun.

Not sure what Dumbo is doing here but it’s nice to see him again.

We saw these dummies in Tokyo too! Will they never learn?

And there’s a bit of monkey business. Luckily, they were quickly dispatched by our skipper’s revolver.

Now that I can say I’ve been on the original Jungle Cruise, I can draw a line though it on my bucket-list. Next item, Pirates of the Caribbean.

Regular readers of this blog will be aware that we had just come from the actual Caribbean and had some pirate action. I was looking forward to this one because it was my first Disney ride back in Tokyo and I disgraced myself by leaving my hat (a baseball cap, not a sombrero or anything) on the ride. We had to hang around until the next ride ended and a helpful employee retrieved it and stuck a “My First Visit” sticker on my shirt. I think it’s so that the other staff could tag me as an idiot and react appropriately, so when she wasn’t looking I peeled it off and stuck it on Duncan. Happy memories, but, clank clank clank splash! The ride has begun.

OK,that looks familiar. I think I saw it on TV?

Boom boom go the cannon. What struck me on this ride, my first Disney ride, in Tokyo is that it was clean, in good repair and not-shit. I always associated amusement parks with ripoffs, decaying attractions and tetanus, like a travelling town show.

This part of the ride depicts the looting of a Caribbean town by pirates. Rum, pieces-of-eight and a jolly good time for all, except the dead townspeople. The Spanish lady being chased around and around by a pirate, presumably to be raped, was a bit of an eye-opener. But, being a politically-correct leftie, I assumed all was well and she was probably into it.

Big Thunder Mountain. Didn’t go on this one but it does look like fun. Now what’s this?

Looks like someone threw out their droid in the underbrush.

Here’s a bunch more of our discarded mechanical friends. I remember the walking wheelie-bin on the right from…

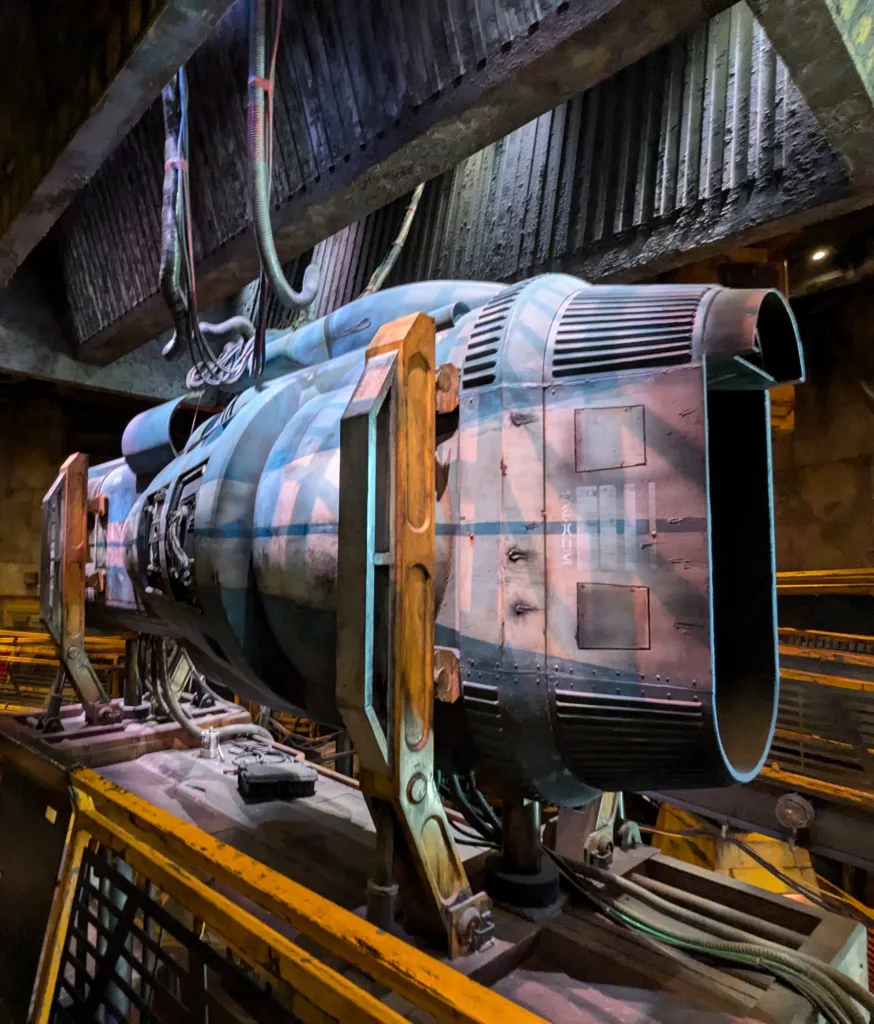

MOS EISLEY SPACEPORT. You will never find a more wrenched hive of scum and villainy. But this is where you’ll find the best freighter pilots. Here’s one now.

“Kessel Run in 12 parsecs? A parallax-arcsecond is measure of distance. Not time, dickhead.” Oh well, let’s get a drink.

Anyhow, it looks like Darth Vader is around. There are hidden speakers playing tie-fighter noises from overhead that lends some atmosphere and there are cast-members getting about in rough-spun cotton robes.

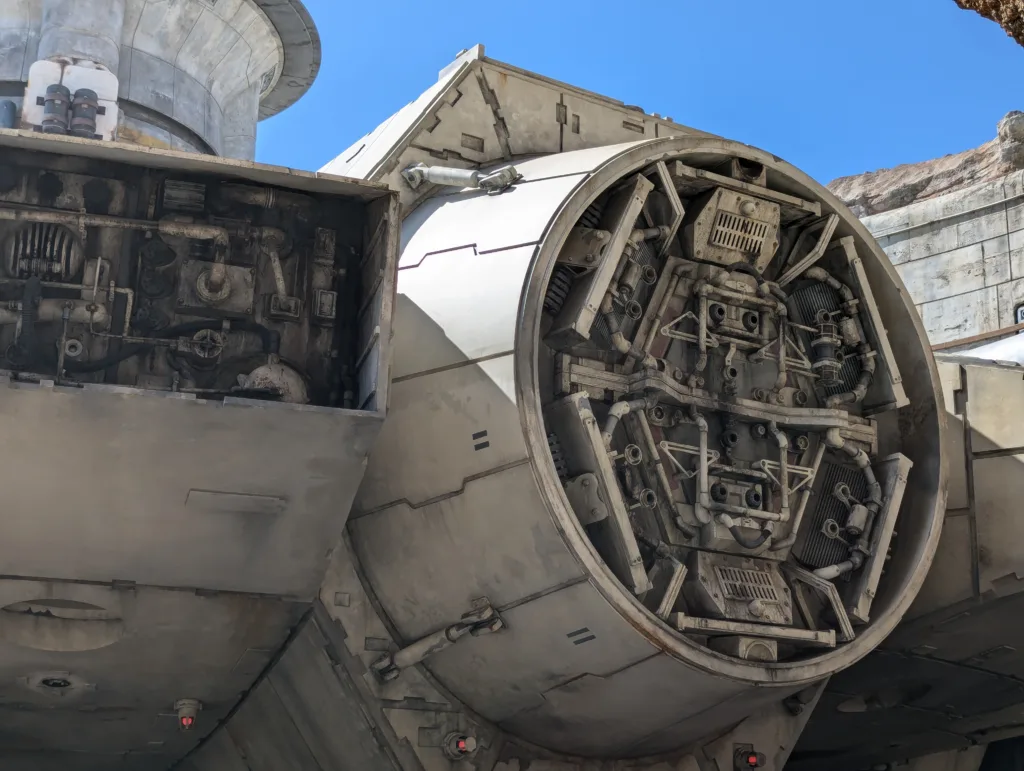

But below is the star of the show. I was lucky to be born in the 70s and experience the first Star Wars trilogy myself. I saw The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi in the cinema when they came out and to this day maintain that the Hoth battle scene was more exciting than losing my virginity. I had lots of the toys, never a Millennium Falcon though. Daniel Panton had one but he had everything and was a terrible bully who would go on to burgle our house in later life. I did have Han Solo in Hoth gear though and a speeder from the same film, which was pretty cool. But seeing this 1:1 model was was remarkable.

And Ted from Idaho is right. Even though the Millennium has a wheelchair ramp I reckon it’s too steep for his rascal.

“I took you to see Return of the Jedi.”

“Oh? Well… Same thing.”

The ‘Falcon really doesn’t disappoint. It’s a faithful model with attention to detail. Here’s some more of that detail.

And from another angle. This is from the queue for the ride, so you get plenty of time to look.

The queue is fairly swift. I guess everybody was at Haunted Mansion. We booked a place in the virtual line-ride for it in the morning, but were eight hours behind.

We didn’t do both Star Wars rides, turns out the big queues were for the other one. Our ride was a four-person crew of pilot, tech and gunners. I was the pilot and kept crashing into stuff.

I’m just going to post a bunch of photographs here because they’re pretty cool.

I think you ride this one like a big floaty moterbike.

On the whole, the attraction leans more into the new movies, which I guess makes sense. But there are a few old icons about.

In the screenplay, R2D2 is introduced as Artoo is a short, claw-armed tripod. His face is a mass of computer lights surrounding a radar eye. I bet they couldn’t find an actor skinny enough to fit into a tripod costume. Didn’t think of that did you, George?

Luke’s Landspeeder is still parked. He left it here a long time ago and is now far, far away.

Not so keen on this one, it has a bunk out front. Can’t be a comfortable ride.

This bit hearkens to an Arabic souk, which fits because it’s all gift shops.

More VR. If you’re on a phone make it full-screen and look around.

And here’s Chewie! You can get a photo with him but I didn’t get close as he can rip people’s arms off.

One last photosphere and let’s move on.

Enough of science-fiction fantasy. It’s time for some real science.

What’s the James Webb telescope doing here? Must be time for another Disneyland classic.

Now that Disney is turning all their rides into movies (and movies into rides) I wonder when we’ll see Space Mountain: Tale from the Beyond the Darkness.

Ready for blast-off.

It wasn’t as scary as I had imagined and Mrs Sachie held my hand the whole time so I wasn’t frightened. With a squeeze and a knowing look, she whispered gently in my ear “Wine tasting at the hotel is in one hour.”

One last stop.

Another last stop at the gift-shop. Sorry Graham and Oil, if you want this one in your collection then you’d better come yourselves.

And it’s goodbye to the happiest place on earth.

The hotel, to add insult to injury (snubbed toes), charges a mandatory $30 daily ‘destination fee’ that you get back as store-credit. Oh, and it expires if you don’t use it on the day. You know, the same way that money doesn’t?

This sucks because there’s no reason to hang out at the hotel when Disneyland (and Califoria Adventure) are right there. I do think it’s this kind of corporate shenanigans that’s at the heart of a dissatisfied and divided America. It’s an obvious cash-grab and break of the social contract. Some can afford it and shrug, some are outraged and will get revenge when they go to the polls next week. Or shoot up a school.

Swapped our JW Marriott scrip for three Hoegaardens , which we actually needed badly, and headed to the complimentary wine tasting. This is valued at thirty of your United-States dollars and was one of the main reasons that Mrs Sachie opted for the JW rather than, say, the more economic Howard Johnson by Wyndham Anaheim Hotel & Water Playground or Anaheim Desert Inn and Suites, which are even closer to the park. And what gorgeous delights did we sip? One blended red and a rosé. Not each, to share.

They were a bit bland and I said so to Elizabeth, behind the bar. So she poured us a domestic cab-sav. Not bad, not bad at all. Then a series of super-Tuscans, which was my first brush with them. Liz saved the day and we retired tipsy and exhausted.

An early start saw us on an 8am, $87 Uber to the airport (!) Queue for miles at check-in and onto a bumpy flight over the Pacific.

My notes finish here, two hours into the flight and 13 more to go. It’s OK, the steward has given me ‘Rhum Wiskey’ and a quadruple vodka. I used the following 9,454km of the flight to stroke my goatee and reflect on the journey. These past two weeks had changed me. I was a wide-eyed optimist when I began, but our travels and tribulations have left me a wiser man. Was the luxury cruse a vapid indulgence of depraved Capitalism? Yes, it was. Did I enjoy it? Every moment, except for vomiting my insides out. I had achieved my childhood dream of going to space visiting NASA and endured two days of weary queuing at America’s pinnacle of culture.

The thing about finally achieving your life’s goals, your great victories, is that at the end, you are changed but the world hasn’t. Your friends and family will be happy to see you, but they haven’t seen what you have seen and can’t understand you the way they did yesterday.

Tomorrow it will be back to the office, where my colleagues will only be dimly aware I have been away. There will be a pile of unanswered mail and projects waiting for me, that prosaic part of living. How could I look at a stuffed inbox and a week of hectic work after experiencing such ecstatic highs and gut-emptying lows that our adventure afforded us? Such things are meaningless, limpid and ultimately trivial.

And so it was, with a heavy heart that I sipped my complimentary vodka, as my beloved wife murmured in her sleep (“Sparkling. Salmon. More shashimii,“) on my shoulder, that I closed my journal on this trip and pondered calling in sick to work on Monday.

Thanks for sticking with me on this epic journey. It’s taken me two years of hard writing, re-writes, drafts and photo touch-ups to get to this point so I hope that you’ve had a few chuckles or yuks.

I don’t write this stuff for money and you’ll never see ads on uncle-Dan’s blog but if you’d like to sign up for my Patreon… Ha ha, just kidding. All an artist really wants is an audience so if you’ve read this far, thanks. Doubly so if you’re not even related to me by blood or law. And if you’re not a relative or close friend, what on earth are you doing here?

The good news is that I have another two notebooks full of adventures to share. Next up is the Taiwan epic. Then… Bhutan!